By Fr David Barry OSB

Monastic life in Western Australia 1846-1870

The first monks to reach Western Australia were, to the best of our knowledge, the Benedictine members of the first missionary party that came with Perth’s first Catholic bishop, John Brady.

The party landed in Fremantle on 8 January 1846 after a voyage of almost four months from England via the Cape of Good Hope.

The group numbered 28 persons, a number of them priests, men and women religious, and a sizeable group of catechists.

Dom Joseph Serra had made monastic profession in his native Spain in 1828 and his confrère, Dom Rosendo Salvado, in 1830.

Shortly after Dom Serra was ordained priest in 1835 both of them, like all the monks and most male religious in Spain, were expelled from their monasteries by an anticlerical government.

Fr Serra went immediately to continue his monastic life in the monastery of Cava, near Salerno, Italy.

Three years later, Dom Salvado followed him, being ordained priest at the nearby town of Nocera early in 1839.

They both lived busy and fruitful monastic lives in the Cava monastery until 1844, when they each confided in one another a call to the missionary life.

When their offer of service was accepted by the authorities of Propaganda Fide in Rome and, reluctantly, by their abbot, they were assigned to Bishop Brady’s Perth-bound party in 1845.

In drawing up his plans for the establishment of missions in his vast but sparsely-populated and largely-unexplored diocese, Brady entrusted the central mission, the third of three, to the Benedictines.

The other two missions, neither of which survived for more than two years, were the northern mission located at Port Essington in what is now the Northern Territory, and the southern mission near Albany.

The general outline of the story of the establishment of New Norcia is well known and need not be repeated here.

What is of interest is the broader monastic life lived in Western Australia during the years in question.

Like other members of the still fledgling Swan River Colony, successive groups of monks and aspirants found themselves faced with all the challenges, difficulties and opportunities that the pioneers encountered.

Like them, the monks were adapting to a very different climate where the seasons were back to front, to a land of strange animals, and to uncertainty as to how they would be able to establish and maintain contact with the Aboriginal peoples of New Holland.

There were additional difficulties due to their nationality and language.

Spain and most things Spanish had been on the outer as far as England was concerned since Philip II and the Spanish Armada of 1588.

They belonged to a Church that in England itself was just beginning to enjoy the results of the 1829 Catholic Emancipation Act.

In addition to being Roman Catholics, they were monks, or aspirants to become monks, which was still a very suspect occupation in the minds of the predominantly Protestant citizenry of Western Australia.

The second missionary party to reach Western Australia came in 1849, this time with the now Bishop Serra.

It comprised some monk-priests as well as diocesan priests, several Italian Benedictine brothers and a large number of Spanish tradesmen who came with the desire to become missionary monks.

The monks had to find somewhere to live when their plans to take up residence in New Norcia were thwarted by Bishop Brady—now decidedly anti-Benedictine—and his agents in early 1850.

Bishop Serra found his band temporary accommodation in Guildford, and from there set out to find a suitable location for a permanent settlement where they could gradually provide themselves with the range and type of buildings normally associated with the European monastic life with which they were familiar.

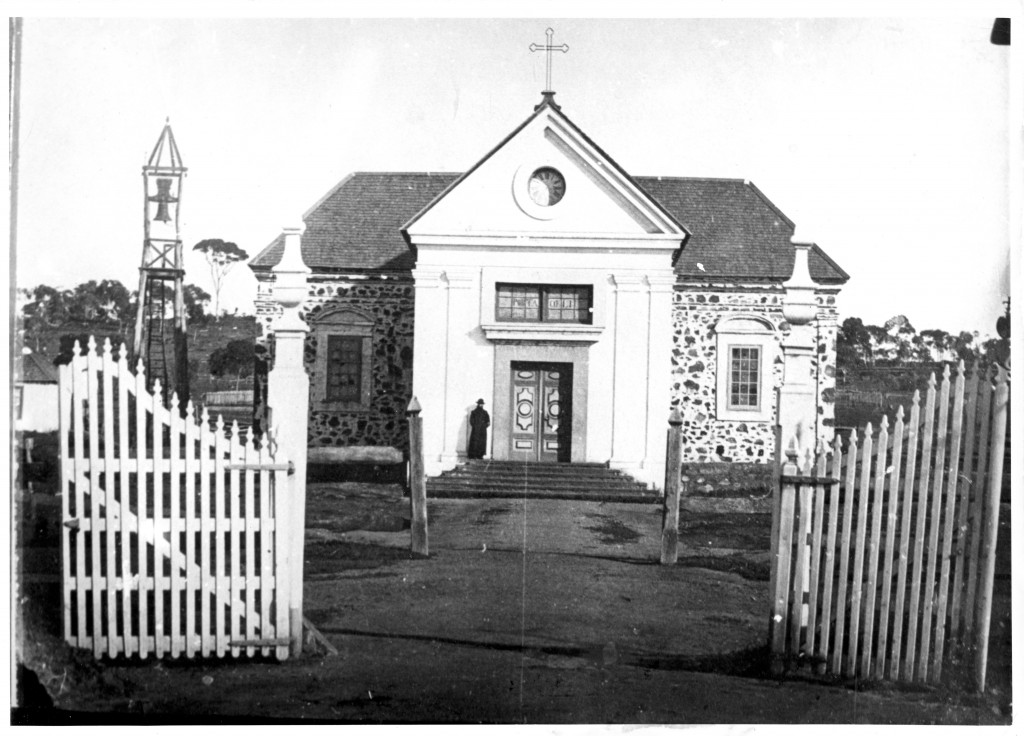

They would need a monastery with an oratory or chapel for liturgical prayer (the Divine Office sung or recited in choir) and personal contemplative prayer to foster the union with God for which monastic life exists, and for the celebration of holy Mass.

This initial, temporary, place of prayer would in time be supplemented and to some extent replaced by a proper church.

They needed to build places for cooking and eating (kitchen, bakery and refectory), for the various kinds of work required for what it was hoped would become in time a largely self-supporting monastic community (workshops, offices, classrooms for novice formation, storerooms, stables), for reading (with a well-stocked library of books suitable to their needs), for extending monastic hospitality to visitors and guests (parlours, guest quarters) and their own living quarters (dormitories and cells, toilet, bathing and washing facilities), and an infirmary in which to care for sick and elderly monks.

It is worth pointing out one unusual characteristic of the New Norcia monastery, where most of the monastic life we are considering was actually lived between 1846 and 1870.

The usual procedure for founding a monastery is that an already existing monastery sends a group of founding monks to the agreed location, with the approval of the local diocesan bishop, and provides the needed support in personnel and finances until the new monastery can reasonably look forward to having a reliable supply of vocations and is able to take on full responsibility for its own financial needs in terms of both capital and recurring costs.

That was not the case with New Norcia. Two monks sent as apostolic missionaries needed some form of monastery to serve as a base for their missionary work among the Aboriginal people.

New Norcia owes its early existence mainly to the generosity of Catholics in Spain, France, Italy and Sicily, some of them well-to-do, many of very humble means even bordering on poverty.

An important source of urgently-needed funds from year to year was the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, established in Lyon in 1822 by Pauline Jaricot for collecting and distributing funds to needy Catholic missions around the world.

From early in New Norcia’s existence, Salvado in particular took steps to ensure that some of the funds received from European donors would be used to procure land, stock and plants for agricultural and pastoral purposes in the hope of ensuring that the mission-monastery could become a self-supporting enterprise, able to pursue its purpose without excessive fear of becoming financially unviable.

The 1850s were uncertain years for most West Australian monks and aspirants. Different perceptions of the primary purpose of their coming to and being in Western Australia emerged between Bishop Serra and his confrère, Bishop Salvado.

Divisions arose between them that inevitably influenced the monks under their care. Bishop Serra was intent on establishing a monastery in Perth called New Subiaco.

As administrator of the diocese of Perth, he could then call on monk-priests to attend to the pastoral needs of a growing Catholic population, as well as having in the Benedictine Brothers a ready supply of tradesmen for his building projects.

Dom Salvado was intent on keeping to their original missionary purpose, with their monastery building complex continuing to be erected at New Norcia.

However, he was kept in Perth by Bishop Serra who found himself embroiled in disputes with the Sisters of Mercy and unable to retain the services and loyalty of some of the veteran Spanish monks who had come with him in 1849 or with Dom Salvado when he finally returned from Europe in 1853.

Charge and counter-charge passed between Rome and Perth, not with the speed of faxes or emails, but with the leisurely pace of the sailing ships and coaches of the era.

It was not until 1859 that the authorities in Rome were sufficiently impressed by Salvado’s insistence (he had finally been allowed to return to New Norcia in 1857) that the mission of New Norcia was separated from the diocese of Perth and the monks stationed at New Norcia and New Subiaco were given a choice of continuing in one or other monastery.

The great majority opted for New Norcia, where the monastic community increased considerably more or less overnight, while the relatively few who chose New Subiaco accepted after a few years that their future did not lie there but in New Norcia.

Given the composition of the Catholic community in Western Australia at the time, Bishop Salvado could not foresee a steady flow of local vocations to the monastic life, and he still had a number of matters to clarify regarding the status of the mission and Monastery of New Norcia.

He set out for Europe again in 1864, by which time he had been keeping a daily diary of events relating to New Norcia for several years, a practice he maintained up to a fortnight before his death on 29 December 1900.

During his absence, the prior, Fr Venancio Garrido, oversaw the continuing development of the Mission, and the final incorporation into the New Norcia community of the last monks to leave New Subiaco, keeping Salvado informed by means of regular and lengthy letters.

Due to yet another revolution in Spain in 1868, which thwarted the completion of his already flourishing plans to establish a novitiate in Spain to ensure a regular supply of missionary monks for New Norcia, Salvado arrived back in Australia in 1869 with more than 30 postulants, most of whom, after their year’s novitiate in New Norcia, made their monastic profession there in 1870, bringing the number in the monastic community to 70, the highest number it has ever achieved.

Salvado had returned to Rome later in 1869 to take part in the First Vatican Council, and received Pope Pius IX’s permission to leave before its conclusion when he learnt of a serious illness that had beset Fr Garrido, who died while Salvado was on the high seas.

We could conclude with this summary comment on the monastic life these men lived. It was in its main lines in continuity with 1,400 years of monastic living according to the Rule of St Benedict – an ordered life of liturgical and personal prayer, holy reading and work in varying proportions according to the seasons, the talents and skills of individual monks, and the particular needs of the monastic community and the surrounding ecclesial and civil society.

Their work involved domestic, agricultural, trade and pastoral work, and it was punctuated with fresh calls on their Christian faith, patience, hope and love and on their resilience as one difficulty and problem was overcome, only inevitably to be replaced by another.

At the end of his long life, Bishop Salvado could write more than once to correspondents, “We seem to be still just beginning. There is so much that needs doing”. For him, it was always, “God alone, and keep going”.

He kept reminding himself and others that nothing worthwhile for God’s kingdom is accomplished in life without “patience, perseverance and prudence”—his oft-repeated “three Ps”, which were always based on a fourth, prayer.