By Callum Ryan,

Office for Film and Broadcasting, Australian Catholic Bishops Conference

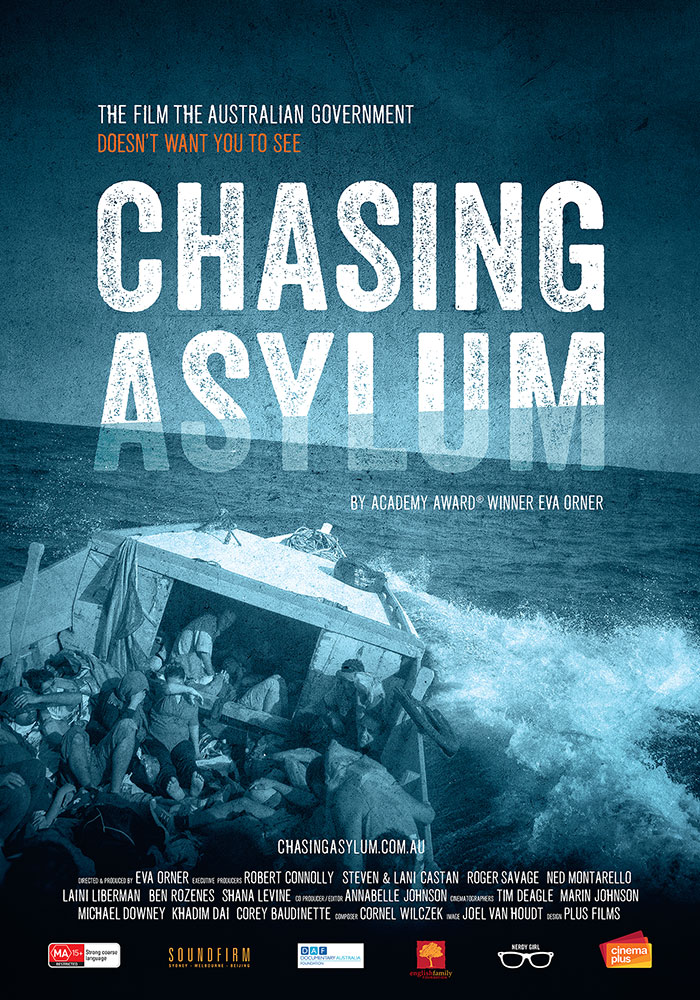

Chasing Asylum documents the lives of asylum seekers sent by Australia’s refugee policy into offshore detention centres on Manus Island and Nauru.

The testimonies of detention centre staff are interspersed with interviews with the displaced people themselves, accumulating their shared distress to powerful effect. What it occasionally lacks in polish or partiality, it makes up for with passion and righteous anger.

The impossible conundrum at the heart of Australia’s policy is as follows: are the deaths of refugees at sea, desperate people exploited by people smugglers, horrible enough to justify imposing such harsh conditions upon refugees who do make the journey by boat to Australia, intended as a deterrent to those tempted to follow them?

Consecutive Australian governments since John Howard, hailing from both sides of the political spectrum, have answered ‘yes’. Attacking the business of people smuggling at its core was the feted intent – if individuals paying to be shipped to Australia are subsequently indefinitely detained offshore, and are even guaranteed not to be able to settle in Australia, then who would willingly pay the high price for a ticket on any people-smuggling vessel?

It is acknowledged early in the film that this policy has achieved its intended result – to intentionally misquote former Prime Minister Tony Abbott, ‘the boats have been significantly reduced’.

However, director Eva Orner is fundamentally concerned with the impacts of this policy on those refugees unfortunate enough to be on its receiving end, now detained in our offshore detention centres with no end in sight.

Orner has managed to secretly film inside these camps and, despite the flashes of shaky-cam-induced nausea inevitable when using small hidden cameras, the footage is provocative. Though often separated from Orner by language barriers, the physical bearing of the detainees speaks loud enough.

As one talking head and former security staff at a detention centre puts it, there is a complete absence of hope. Men, women and children alike – these are people without a foreseeable future. Several social workers sent underprepared to the centres vouch for the daily struggle that these people face to even find the will to continue living.

The sanctity of human life and the obligation that we all share to treat others with dignity cannot be overstated. When the credits roll by, Chasing Asylum cannot offer a solution to the catch 22 at the heart of Australia’s refugee policy. Is the answer to accept and resettle all refugees coming by boat, thus bolstering the dangerous operations of criminal people smugglers?

Or is the answer to continue along our internationally maligned path, and let those who have already come suffer to save those who are deterred from coming by sea in future? This is not to suggest that the film ought to have a solution – it has been a demonstrably difficult issue in politics for decades.

Orner has come to the subject with a noble agenda, shining a light on the flesh and blood human beings who suffer under the policies made by comfortable politicians holed up hundreds of miles away. Her mission in making the film has been well addressed, and viewers will be hard-pressed to forget it when next discussing refugees in our country.

With all that said, the documentary can fall short of cinematic greatness. The stunning opening shot from on board a people smuggler’s vessel is soon replaced with more conventional lensing of interviews and daily life. The editing, while internally consistent, can leap through the various threads somewhat haphazardly.

This reviewer was a member of the Ecumenical Jury at the Berlin Film Festival in February, after which our Jury Prize (and the Golden Bear no less) was awarded to the Italian documentary Fuocoammare. It shared a similar subject, chronicling the intersecting lives of refugees and locals on the Mediterranean island of Lampedusa, both circles connected through the local doctor who shepherds them through life.

However, it refrained from including interviews, instead relying on its powerful, haunting visuals, woven together with the camera as a silent observer. This more meditative, cinematic approach may have helped Chasing Asylum avoid feeling like an extended episode of Four Corners. Any emotion that the film conveys loses some poignancy when it’s constantly accompanied by signposts as to what and how great your emotions should be.

Callum Ryan is an associate of the Australian Catholic Office for Film and Broadcasting.