By Hal Colebatch

The establishment of the Catholic Church in Western Australia was met by a series of hardships.

These were due not principally to sectarianism but to the remoteness and isolation of the colony, and were compounded by unrealistic administration.

In New South Wales, there had been many Irish Catholic convicts, many of whom, upon obtaining freedom, made important contributions to the colony’s life and some of whom became wealthy and successful.

There were also many Irish Catholics among the soldiers of the relatively large garrison.

When Catholic priests arrived in New South Wales, they found quite a large Catholic congregation awaiting them.

By the 1840s, there was a fairly large settled area and infrastructure. None of this was the case on the western side of the continent.

We know from the census of 1848 that at that time there were 1,148 people in Perth, with 126 Catholics. The total number of Catholics in the whole colony was 337.

Further, the Church in its earliest days in WA was in the care of a man who, though undoubtedly of deep devotion, was by all accounts not the man for the particular demands of this job.

Fr John Brady was an heroic but tragic figure.

John Brady was born in County Cavan, Ireland around 1800 and, while it is believed he studied for the priesthood in France, this is not proven.

After ordination he had volunteered for missionary work. He is said to have won golden opinions from clergy and people for his priestly character and self-sacrificing devotion.

In New South Wales, he was dean of Windsor and his parish included Penrith and all branches of the Hawkesbury from Windsor to Broken Bay.

His charges were mainly Irish convicts assigned to the landholders, and he rode hundreds of miles a month to serve them.

He was instrumental in establishing the convicts’ right to freedom of worship. A judge, Justice Filhole, recorded in 1836: “He is the true type of Catholic Priest, perfectly unselfish. He gave everything he had to relieve the poor and to educate the children of the parish.”

In 1839, Dr William Ullathorne OSB had written: “Father John Brady is a man I revere as a Saint …” In the same year, Archbishop Polding had written of him as “labouring with the zeal of an Apostle in his immense district”.

With a Belgian priest, Fr John Joostens, and a catechist, Patrick O’Reilly, he arrived in Albany on 4 November 1843. He continued by sea to Fremantle in December.

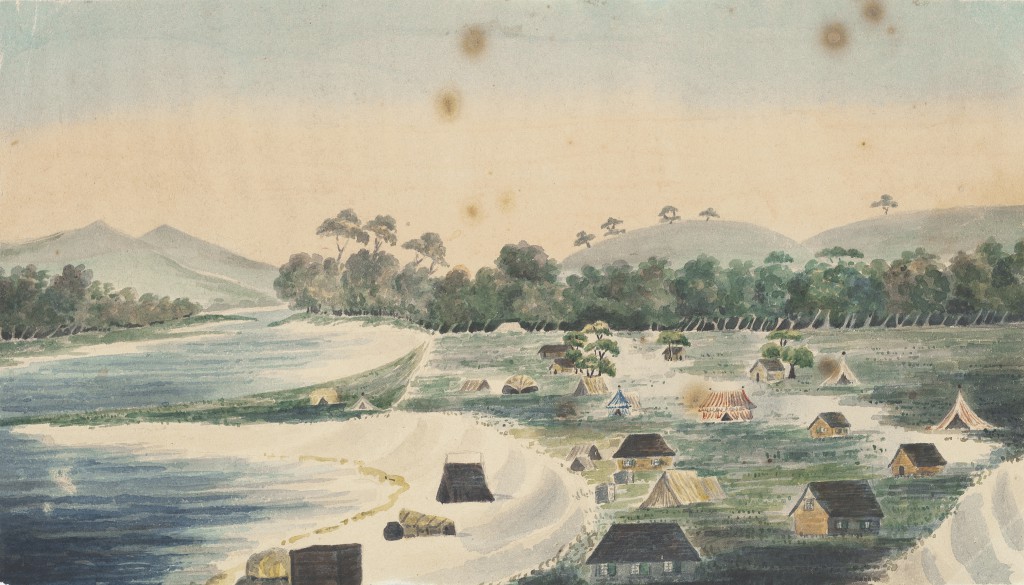

The Swan River Colony was in a bad way at this time. Its population numbered about 4,000. There was almost no labour to work the land, and many of the settlers did not have farming skills.

The few Catholics in the Perth area were mostly of the poorer class. Governor John Hutt received Fr Brady with cordiality, and assigned him some land on which to build a church.

Non-Catholics were generous in supporting the venture, including financially. The building was begun on the Feast of St John the Evangelist, 27 December 1843.

Fr Brady visited Rome the following year and asked that a new diocese be created for WA, with a bishop resident in Perth. He said there were 5,000 Europeans in WA and gave an estimate – impressive but wildly inflated – of two million Aboriginal people (this figure had, according to some sources, been given to him by Governor Hutt).

Authorities in Rome apparently accepted an estimate of 3,000 or more Catholics in WA, although the true number was only a tiny fraction of this.

Plainly, Brady saw missions to the Aboriginal people, whom he believed to be present in great numbers, as of the highest importance.

Thus, in addition to the task of establishing the Church in what was little more than a wilderness, he set out to bridge a cultural gap.

In any event, Rome agreed that a new diocese was to be established. Brady, who was perhaps aware of his own unsuitability for the position, nominated Dr Ullathorne to be the new bishop but Ullathorne declined, and Brady himself was appointed, Ullathorne having recommended him as a very good missionary priest.

Though Brady was a man of extremely simple life and a fine missionary, he was quite unsuited to the difficult administrative and financial tasks that would inevitably confront him in such a position.

Indeed, it was suggested by one observer, the Catholic Colonial Secretary Richard Madden (later knighted), who saw a great deal of Brady and who admired him in many ways, that the extreme austerity of the life he lived was such that “The belief seems to have grown in him that all other persons in religion about him or connected with the mission (however differently physically constituted) could have no other desire and were capable of living as he did”.

“This was a great mistake, and it led to all the difficulties that took place.”

Archbishop Polding in Sydney, who had come to know Brady well, but who had not been consulted on his appointment, and whose diocese had previously covered the whole continent, was disturbed when he heard the news of Brady’s appointment.

He had doubts about Brady’s capacity and prudence. He had, he believed, zeal but no discretion. Nevertheless, he told Rome he would give Brady all the aid and welcome possible.

While in Rome, Brady set about recruiting new clergy for WA. These included two Benedictines who had fled religious persecution in Spain: Jose Maria Serra and Rosendo Salvado, who would prove to be among the influential figures of the Church in WA.

Others recruited were an Italian priest, Fr Angelo Confalonieri, and a layman, Nicola Caporelli, who bore the title ‘Count of the Papal States’.

Bishop Brady then travelled to France where he obtained six more recruits – three priests, two lay brothers of the Missionary Society of the Holy Heart of Mary and a Benedictine novice from Solesmes. In England, he recruited a subdeacon, Denis Tootle, from the Benedictines at Downside.

All the recruits would prove to be long-standing friends to the Australian mission. From Ireland, he recruited another priest, Peter Powell, eight student catechists, six Sisters of Mercy and one postulant – 28 in all.

With hindsight, Bishop Brady would have done better to settle for a smaller party, which the tiny Catholic population of Perth and such outlying settlements as there were could have supported more easily.

They had come to serve a people who largely did not exist, and in numbers that might be expected to unnerve some of the Protestants – as well as the few Catholics who would have to support them.

Only a small number of the priests of the party could speak English, but Brady apparently did not consider this a problem because he saw the greatest thrust of the Church’s work to be among the Aboriginal people.

It did, however, make interaction with the white settlers upon whom they depended more difficult. The fact that Latin was the common language of the Mass was important but not enough to overcome this problem.

Bishop Brady’s party sailed for Fremantle from England in the vessel Elizabeth, and arrived in Gage Roads on Wednesday, 7 January 1846, landing the next day.

Though Fremantle looked bleak and depressing in the January sun, the party had a pleasant trip up the Swan River on Friday, 9 January.

A crowd waited to greet them at the Perth jetty and they received a cheer. They landed, formed a procession, and moved off up the sandy main street in the direction of the unfinished church, singing litanies.

As the party had arrived sooner than expected there was no accommodation arranged for the sisters. However, a Mrs Crisp, a Methodist who ran a boarding house, gave them lodgings, and was ever afterwards a friend to them.

The first cathedral, St John the Evangelist, had its inaugural High Mass on Sunday, 11 January. The church reflected Bishop Brady’s value of austerity as well as the poverty of the colony.

Apparently there was a long, low lean-to building attached to the north wall. On the south side there was a small windowless room for a priest’s lodging. Bishop Brady lived there for several months.

The Mercy Sisters, themselves by no means living in luxury, were touched by the privations endured by the bishop. He moved for a time to a larger room but gave this up for use as a schoolroom.

He then moved into the belfry, a little wooden building, though its scanty boards allowed free access to the weather on all sides. He slept in an armchair.

During the rainy season he moved to another box-like room where he slept on a sofa under an umbrella.

The rest of the colony would doubtless have been ready enough to criticise a Catholic bishop who lived in wanton luxury, but these extremes must have seemed bizarre to many.

With the arrival of Bishop Brady’s party, it might be said that the Catholic Church had established a considerable institutional presence in the tiny colony, but it was one which was unbalanced. Sadly, one of the missionaries from Amiens, Fr Maurice Bouchet, died on 24 January, aged 24. He was buried close to the little church.

While the general population of Perth seemed friendly, there was also apparently a good deal of anti-Catholic feeling in the Irish Protestant upper circles of the colony.

This cannot have made the beleaguered Bishop Brady’s task any easier. Brady made drastic mistakes, but he did somehow lay the foundations. He was probably meant by nature to be a missionary, but he was no administrator.