By Dr Christopher Dowd OP

Conflict is a major factor in human relationships and a driving force behind the course of history.

It is prominent in the early history of Western Australian Catholicism.

Catholics were present, as far as we can tell, from the very start of the Swan River Colony, founded in 1829.

They were left to their own more or less harmonious devices until 1843 when, at their own repeated insistence, the archbishop of Sydney, John Bede Polding, who was responsible for the ecclesiastical government of the entire continent of Australia and its adjacent islands, despatched their first priest.

This was the Irishman Fr John Brady, who was to provide pastoral care for the far distant Catholic community in the west.

Hardly had Fr Brady arrived and taken a quick look around when he left again and travelled to Rome where he persuaded the authorities in May 1845 to establish a new ecclesiastical jurisdiction, the diocese of Perth. Brady was appointed as the first bishop.

He promptly set off on an extended recruiting and fundraising campaign around Europe. Among the missionary group he assembled was a Spanish Benedictine monk, Jose Maria Serra, who, together with companions having been expelled from Spain by an anti-clerical government in the 1830s, had taken refuge in a monastery near Naples.

The relationship between Brady and Serra now moves into the foreground of Western Australian Catholic history, a relationship dominated by bitter controversy and sometimes violent disagreement.

Very soon after the return of Bishop Brady with his missionary team, the affairs of the Catholic Church in Western Australia took a sudden and serious turn for the worse.

His report to Rome on the circumstances of the new mission territory had been wildly exaggerated to the point of fantasy.

Consequently, he recruited a grossly inflated workforce which the miniscule Catholic community was unable to support.

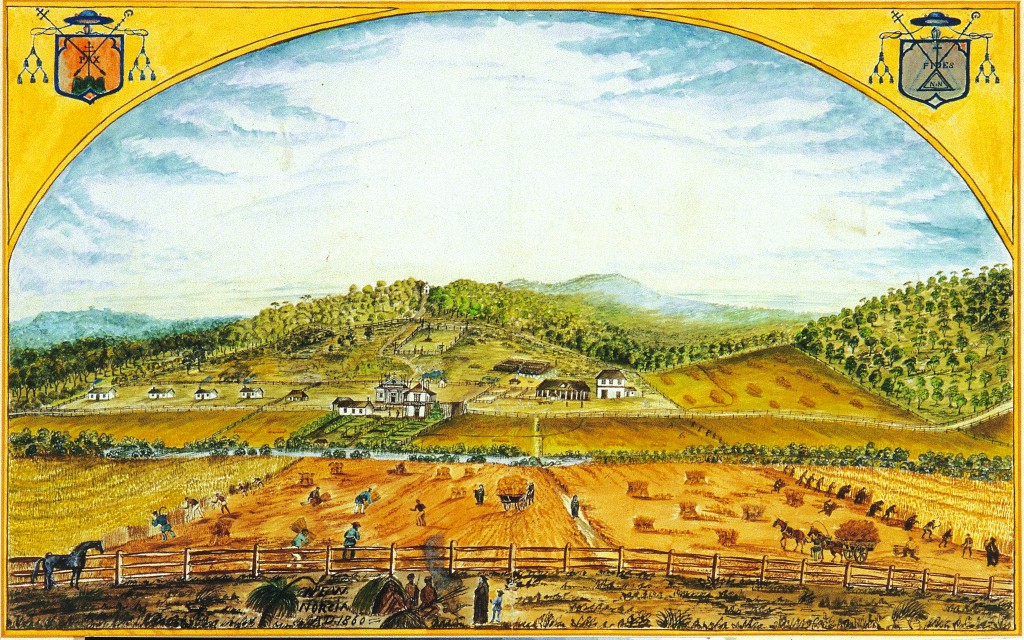

Every part of his hopelessly-ambitious scheme, ranging from Albany in the south to Port Essington (near modern Darwin) in the north, failed except for New Norcia where Serra’s Benedictines founded a monastery and managed to hang on.

Brady resorted to business dealings in land and livestock to fund the diocese but these, too, failed and he was soon carrying a catastrophic level of debt.

Trouble with Serra first comes into view when, in letters sent to Rome, Brady threw the blame on to others, particularly the Spanish Benedictines.

Besieged by creditors, the bishop sent Serra to Europe early in 1848 to raise funds to stave off the total financial ruin of the Western Australian mission.

However, on arrival in Rome Serra found himself appointed as bishop of Port Victoria, a new diocese in the Port Essington district on the northern coast of Australia that had been recommended by Archbishop Polding.

When Brady heard of Serra’s elevation to episcopacy, he assumed that the funds collected would be diverted from Perth and applied to the new bishopric.

Resentful that Serra had not done what he had been sent overseas to do, Brady sent another Spanish Benedictine, Serra’s colleague, Rosendo Salvado, to collect money for Perth itself.

He also applied to Rome for the appointment of Salvado as a coadjutor or assistant bishop to ensure that the funds that Salvado raised would be for the benefit of Perth.

Rome had other ideas. It decided that Brady’s coadjutor should be, not Salvado, but Serra, who had already amassed a very large amount of money, and that Serra should have the entire charge of the temporal affairs of the diocese of Perth to compensate for Brady’s bungling. Salvado would be transferred to the diocese of Port Victoria.

This complicated plan was adopted, despite warnings that Brady had specifically asked for Salvado, did not get on well with Serra, would be humiliated by having the temporal government of the diocese taken out of his hands, and that it was unethical to divert monies collected for one cause to a different cause.

The absurdity of having three bishops for a region in Australia in which the Catholic population had probably not yet exceeded 500 was not lost on Bishop Francis Murphy of Adelaide who commented wryly that there was “a number [of bishops] sufficient to convert the whole colony black and white”.

At first all went well between Bishop Brady and Bishop Serra when the latter returned to Western Australia at the end of 1849 with a pile of money and a fresh cohort of missionary workers.

However, as soon as Serra paid off the diocesan debt, Brady’s attitude changed completely.

He appointed as his vicar general the possibly mentally unstable Fr Dominic Urquhart who had been recruited by Serra from an Irish Cistercian monastery but quarrelled with him bitterly on the voyage out.

Brady launched legal action against Serra in the civil courts for control of diocesan assets and summoned a diocesan synod at which Serra was vilified and excommunicated, forcing him to retreat to New Norcia from which he and the Benedictine community were subsequently expelled at gunpoint by Brady’s agents.

Brady wrote often to Rome urging that Serra be sacked and decided to follow this up with a personal visit to the city.

Throughout the greater part of 1850, Brady’s agent in the absence of the bishop, Urquhart, pursued Serra relentlessly and aggressively through the courts and the press for control of the property of the Church.

The Roman decree appointing Serra as temporal administrator of the diocese was ignored. In Rome, Brady’s mission was a failure.

Roman officials had tried to be even-handed but the evidence for Brady’s disobedience, belligerence and incompetence was overwhelming.

Not only was Urquhart dismissed from his offices and ordered to leave Australia, but Brady was deprived by a papal decree of June 1850 of all powers belonging to the bishop of Perth, spiritual as well as temporal, which were transferred to Serra.

Brady was left with the title ‘bishop of Perth’ only and narrowly escaped deposition.

Furthermore, he was forbidden to return to Australia. Brady ducked and weaved to avoid these commands and censures and eventually ignored them, taking ship for Western Australia in September 1851.

A panicked Rome moved to protect Serra by appointing him apostolic administrator of Perth.

When Brady arrived towards the end of the year, the struggle with Serra was resumed and the Catholic community in Perth tipped over into anarchy.

Violent brawling between the two bishops’ respective adherents for possession of the cathedral, the bishop’s residence and other ecclesiastical buildings required the intervention of the police.

When the papal documents conferring all diocesan authority on Serra arrived in Perth in April 1852, Brady argued incoherently that since they addressed him as bishop of Perth, he still held the jurisdiction attached to the office.

With Serra pleading exhaustion, helplessness and inability to deal any longer with a state of affairs that he justifiably termed a schism and Brady intransigent, pugnacious and defiant even towards the command of the Holy Father himself, Rome came to the realisation that, having exhausted all other avenues, only some kind of local, personal confrontation of Brady in Western Australia with papal authority could bring him to heel.

Hence, Rome deputised Archbishop Polding to undertake the arduous journey by ship and horse from one side of the Australian continent to the other.

Although bitter and resentful, Brady had no alternative under these circumstances but, on 4 July 1852, to submit formally to the papal will, apologise for the disruption and scandal he had caused and unreservedly hand over to the archbishop all financial and property claims.

Brady left Western Australia forever the following month and spent the rest of his uneventful life in semi-retirement in Ireland and France, supported by a generous pension supplied by the impoverished diocese of Perth.

He was allowed to keep the title ‘bishop of Perth’ to the end of his days which came in 1871.

Serra governed the Church in Perth as apostolic administrator until 1862 when he resigned and returned to Spain. He died in 1886.

The chaos in the Western Australian Church in the late 1840s and early 1850s was caused by a complex number of contributing factors, not the least of which was a clash of personalities.

The evidence for John Brady’s character is very patchy but he was a complex man. He was a dedicated, self-sacrificing and hardworking if impractical pastor, but ambitious and self-willed, imprudent and stubborn, aggressive and persecuting towards enemies. His persistent uncooperativeness with higher authority was spectacular.

Polding wondered if Brady suffered from a mental malady that was said (with little evidence) to run in the Brady family.

Brady’s alliance with the fiery, obsessive Dominic Urquhart could well have been a meeting of like minds.

Not unreasonably, Serra presented himself as a victim during the Brady years, but Serra’s personality, too, was difficult: authoritarian, vain, imperious, bad-tempered and touchy, as some Western Australian Catholics discovered when Serra inherited the apostolic administratorship of the mission on Brady’s departure.

National differences between the Irish and Spanish doubtless added fuel to the explosive mix, a point which Brady manipulated in his local politics and Roman correspondence.

On the other hand, shared nationality did nothing to temper Serra’s quarrel with his fellow Spaniard, Rosendo Salvado, sustained through the 1850s.

The exclusion of Polding as metropolitan of the Australian Church from early decision-making about the diocese of Perth was a Roman mistake, contrary to the normal procedures of advice and consultation in such cases.

Polding’s hitherto high reputation with Rome was already in decline and Brady worked hard to persuade Roman officialdom to leave Sydney out of the calculations.

But, in the end, Rome had no option but to turn to the archbishop to subdue Brady and restore ecclesiastical law and order in Perth.

On the other hand, maybe Polding should take some responsibility for the fiasco in appointing Brady to the leadership of the isolated Swan River Colony mission in the first place.

Also significant in explaining the prolongation of the Perth ‘schism’ was the primitive quality of mid-19th century communications.

Around 1850, a full turn-about of correspondence between Australia and Europe could not be achieved in much less than nine months to a year.

The ponderously slow rate of communication was exacerbated by Brady and Urquhart playing fast and loose with Roman letters, pretending not to have received instructions.

The sheer distance of Perth from Rome – and to a lesser extent from Sydney – gave Brady a sense of invulnerability which he exploited to the full.

In the end, whatever the allocation of blame should be, the long, drawn-out and ferocious fight between John Brady and Joseph Serra and aspects of the personalities of the two bishops hindered the progress of the Catholic community and institutions of Western Australia for the first 20 years or so.

It was only when both of them were off the scene and leadership of the Catholic community passed to another Spaniard, the diocesan priest Martin Griver, that the Western Australian mission started to move forward.