By Carol Glatz and Cindy Wooden

The Sistine Chapel’s transformation from a world-famous tourist site to the prayer-filled space where cardinal electors will choose the next pope is under way.

Vatican workers have begun installing protective panels to cover the mosaic tile floors, and mini-scaffolding will raise a false floor level with the altar and eliminate any steps.

Workers will then have to put in tables and chairs for the expected 115 cardinal electors.

Like for the 2005 conclave, two stoves will be installed: one to burn ballots and the other to burn chemicals to create different colored smoke to let the public know if a pope was selected or not. Father Lombardi said that burning the ballots with wet or dry straw had made the right color, but never really created enough smoke to offer a clear signal.

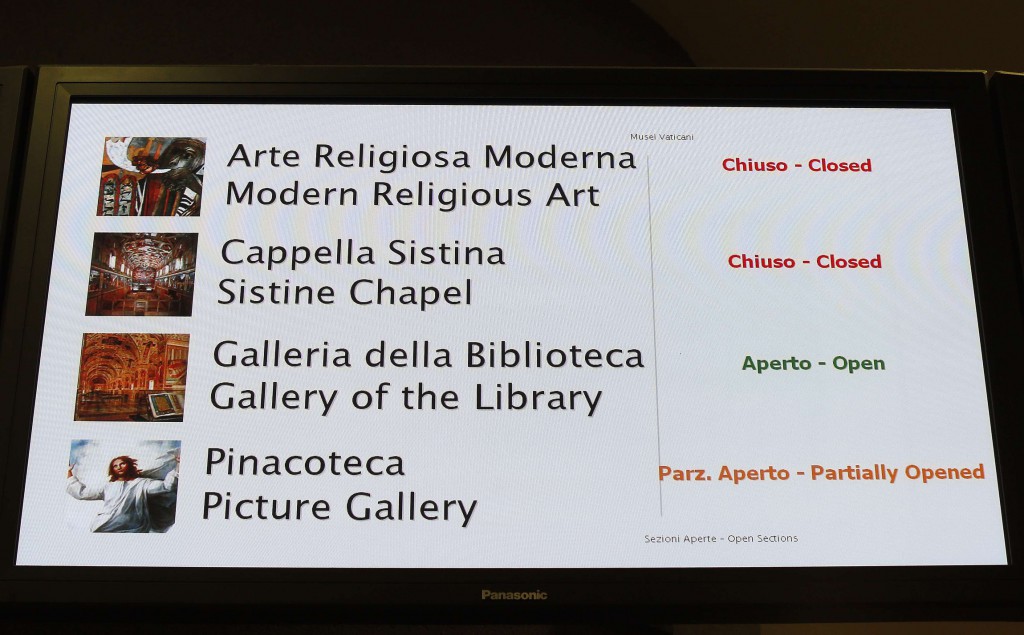

In order to begin the preparations, the chapel, where the conclave will take place, was officially closed to tourists March 5.

Maintaining secrecy is part of the cardinals’ oath, and technicians sweep the chapel for electronic surveillance or recording devices before the conclave.

Jesuit Father Federico Lombardi, Vatican spokesman, told journalists March 6 that jamming devices are used to disable cellphone signals, but that they are not installed under the false flooring as had been reported in the past.

However, even the innocuous climate sensors dotted about the chapel will be dismantled to remove any suspicion of being spied on, said Antonio Paolucci, director of the Vatican Museums.

The head of the Vatican police, Domenico Giani, said it would be a good idea to take them down, “perhaps to avoid every feeling and fear, too, of Big Brother,” Paolucci told the Italian newspaper Il Messaggero March 6.

Even though the sensors don’t present a security risk, the head of the Vatican police force “wanted to avoid even what might be the most minimal psychological discomfort,” the museums’ director said.

The sensors were eventually going to be replaced anyway, he said, when the museums install a new climate-control system for the chapel.

Security concerns are so tight that it looks as though, during the voting sessions, cardinals will not be allowed to use the museum lavatories, Paolucci said.

“Something different has been decided on; I believe they may be installing portable chemical toilets inside the chapel,” he said.

A few other areas of the Vatican Museums will also be closed in the run-up to and during the conclave because of their proximity to the chapel, he said.

Cordoned off to the public will be the Borgia apartments, the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Matisse and Manzu halls, he said.

Though they blocked reservations for visits to the chapel as soon as retired Pope Benedict XVI announced his resignation Feb. 11, Paolucci said, the museums still had to spend weeks contacting individuals and groups who had already made advanced reservations.

More than 5 million people stream through the Sistine Chapel each year, and many were bound to be disappointed the chapel would be closed for an unspecified amount of time in March; however, people have been very understanding, he said.

“If the Sistine Chapel were closed because a custodian called in sick, then they would complain, but in this case, they get it,” he said. – CNS

From the outside, the only sign of the conclave proceedings will emerge from the smokestack on top of the chapel’s roof. Barely visible from St. Peter’s Square, it is kept in the viewfinder of telephoto lenses until a new pope is elected and white smoke pours out.

Inside, the cardinals will be immersed in a setting resplendent with art — surrounded by visual reminders of humanity’s destiny and the church’s history.

The cardinals file into the Sistine Chapel, passing beneath Michelangelo’s frescoed interpretation of the beginnings of salvation history: creation, the fall of Adam and Eve and the flood.

They will be flanked by paintings of God’s attempts to win back his people and save them: on one wall, the life of Moses; on the other, the life of Christ, including a painting of him handing over the keys of heaven and earth to St. Peter, the first pope.

Past the table where the cardinals will deposit their ballots and behind the main altar rises Michelangelo’s massive reminder of how each person will end his or her days: “The Last Judgment.”

Even after the Sistine Chapel was built and its decoration completed by Michelangelo in 1541, not all papal elections were held in the chapel.

Pope Pius VII was elected in Venice, Italy, in 1800.

The four conclaves that followed (from 1823 to 1846) were all held in Rome’s Quirinal Palace, once the summer home of the popes and now the residence of the president of Italy.

While the art and fame of the Sistine Chapel make it almost unthinkable that a conclave would be held anywhere else, the chapel presents two small problems.

The first is space. At the 1978 conclaves that elected Popes John Paul I and Blessed John Paul II, some of the 111 participating cardinals complained that their seats were so close together they barely had room to breathe, let alone write a secret ballot.

While the chapel has about 5,600 square feet of floor space, the room is divided by a marble and iron screen, halving the space for setting up tables and chairs in a way that allows all the electors to see each other and the altar.

The smoke signal — the only form of communication between the electors and the outside world — also proved problematic in 1978.

A special stove and chimney were installed in the chapel in the middle of the 18th century.

The black smoke, which signals a ballot without a definitive outcome, was produced by burning the ballots with wet straw or, later, by adding chemicals. The white smoke that tells the world a new pope has been elected is produced by burning the ballots alone.

But weather, atmospheric conditions and pollution all make the signal difficult to decipher.

For the 2005 conclave, the Vatican decided the election of new pope would be announced by the joyous ringing of the bells of St. Peter’s Basilica, as well as the traditional white smoke from the chimney, in order to remove any doubt about the voting results.