By Patricia Zapor

As Georgetown University law professor Michael Gottesman put it, the people who lined up outside the Supreme Court for days to be able to watch a legal argument about the validity of same-sex marriage must have been surprised to find half the court’s time devoted to debating legal standing, jurisdiction and states’ rights versus federalism.

Gottesman opened a March 27 panel discussion at the Georgetown Law Center about oral arguments in two cases related to same-sex marriage heard at the court that day and March 26 by observing that both cases may well be decided over legal questions unrelated to marriage.

That was surely surprising, Gottesman said, to the people who camped out for days to get seats at the arguments and the thousands of people on either side who rallied outside the courtroom. They may have been somewhat puzzled that what the public sees as the core issue — should same-sex couples have a uniform right to marry — barely come up at all.

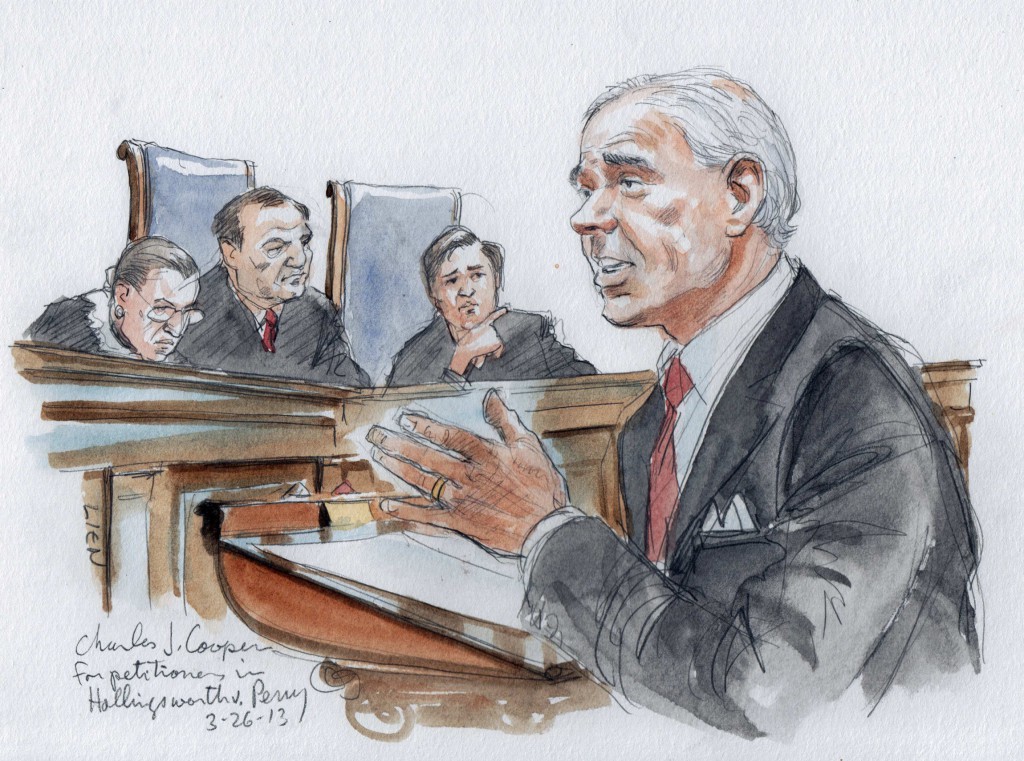

Instead, in Hollingsworth v. Perry the court may rule on California’s Proposition 8, which banned same-sex marriage, on the basis of whether it was proper for the people who put the 2008 initiative on the ballot to appeal the federal District Court ruling that said the law is unconstitutional. Before Prop 8 passed in November 2008, about 18,000 same-sex couples got married, after the state Supreme Court ruled in June 2008 they had the right to do so.

Because California’s governor and attorney general declined to argue in support of Prop 8, the District Court and the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals allowed Dennis Hollingsworth and other proponents of the ballot measure to make the legal challenge.

If the court rejects Hollingsworth et al. as petitioners, that would mean the District Court’s decision that Prop 8 is unconstitutional stands and same-sex couples in California may marry. Such an action would affect only California. And the Supreme Court would sidestep a ruling on whether there is a federal constitutional right for same-sex couples to marry. The same result could occur if the court said it was too hasty in taking the case — the terminology is “improvidently granted.”

In United States v. Windsor, heard March 27, the justices spent nearly an hour debating whether a group of members of Congress may legitimately argue in support of a law they passed, but which the executive branch of the federal government — the Obama administration decided it is unconstitutional — declined to support in court.

The Defense of Marriage Act, known as DOMA, is a 1996 law that says no state must recognize a same-sex marriage from another jurisdiction. So, the 36 states that do not allow same-sex marriages need not acknowledge same-sex marriages from the nine states and the District of Columbia where they are legal.

DOMA was challenged over another provision, which says for the purposes of federal benefits and obligations, the term marriage applies only to heterosexual pairs. The lawsuit arose when Edith Windsor’s spouse, Thea Spyer, died and Windsor was held liable for $363,000 in inheritance taxes. Had her spouse been male, there would have been no tax.

Though the federal government, as the Internal Revenue Service, imposed the tax, when a District Court and the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals found in Windsor’s favor, the Justice Department agreed with the ruling, but still asked the Supreme Court to weigh in on the case.

In arguments, Justice Anthony Kennedy said the administration’s complex approach to the case “would give you intellectual whiplash.”

As Gottesman said, the crux is: “The government threw in the towel” on both cases.

Should either or both of the cases survive those questions and there are rulings on the merits of the underlying issues, it’s quite possible that the court still will decide narrowly, staying away from that core question that the general public is expecting the justices to address.

In the oral arguments, justices who otherwise seemed to have clear opinions about whether same-sex marriage should be legal seemed less convinced that a decision about it for the whole country is theirs to make — at least not yet.

That was another lengthy thread of debate in both cases, whether there’s a clear enough sense of the nation’s will on same-sex marriage for the court to step in and rule for the whole country.

As Justice Samuel Alito put it in the Hollingsworth argument:

“You want us to step in and render a decision based on an assessment of the effects of this institution which is newer than cell phones or the Internet? …We do not have the ability to see the future. On a question like that, of such fundamental importance, why should it not be left for the people, either acting through initiatives and referendums or through their elected public officials?” – CNS