By Hal Colebatch

It is worth considering the social conditions of the earliest days of Western Australia to gain an understanding of the hardships under which the first Catholic missionaries laboured.

The period of approximately three decades from the foundation of the Swan River Colony in 1829 to the introduction of convicts was a time of struggle for all and widespread poverty for some.

It seems astonishing today that settlers landed on a sandy coastline without an acre having been surveyed or a building erected. Only the slightest knowledge had been obtained of the soil, climate, products or inhabitants.

There was almost no labour to work the land or to build up infrastructure. Although there was virtually unlimited land available, there were great difficulties over its allocation at first and accusations that the government had retained all the arable land for members of the aristocracy.

Further, of course, much of the land was of little use due to a lack of roads.

The remoteness of the colony meant that it was outside most of the world’s trade routes. For many of the settlers, largely members of the British middle class, the culture shock must have been terrifying.

However, many of the men were also veterans of the Napoleonic Wars and the tough campaigning of the Iberian Peninsula.

The colony might easily have failed completely and been abandoned. It would not have been the first or last time such a thing happened.

That it did not fail was a tribute to the courage and endurance of the settlers who made it through every kind of disappointment and frustration.

Letters home as early as 1831 and 1832 speak of enjoyment and gaiety, as well as the fact that when provisions from Britain failed to arrive, the colonists made a good fist of growing their own produce.

At the end of 1830 the Swan River Colony numbered 1,767 souls. Ten years later it still numbered less than 2,000 and, 20 years later, it was only 4,622. However, farming, particularly wheat and sheep, was doing well.

As described in the official centenary history, A Story of a Hundred Years: “In 1836, when people in England were talking of the complete failure of the settlement, a cargo of wheat was sent from Western Australia to New South Wales, where a severe drought was experienced.”

As far as sectarianism goes, one does not get an impression of great sectarian bitterness except possibly among some of the Anglo-Irish officials.

The Anglican Church received some official favouritism and, in the future, there lay the long, long battle for State aid to the Catholic education system.

There seems to have been many instances of Catholic and Protestants cooperating with and helping one another.

In the circumstances, they probably had little choice.

In 1849, the settlers petitioned the British government for convicts. This coincided with the abolition of convict transportation to New South Wales and the request was accepted with alacrity.

Transportation to Western Australia went on for 18 years, and there is no doubt that it transformed the colony.

In addition, there were many free Irish immigrants – the fact that many of these were women being particularly important. JT Reilly, a prominent Catholic and newspaper editor, has stated that marriages between the Irish girls and ex-convicts were ‘nearly always happy as well as lasting’.

In 1848, of a total white population of 4,622, there were 337 Catholics in the colony, 213 of these living in the Perth area, the rest very thinly scattered through the few outlying settlements and farms.

By 1854, there were 2034 Catholics out of a population of 11,976.

There were 455 Catholics living in Perth and 258 in Fremantle, as well as 279 Catholic soldiers and 431 Catholic convicts.

By 1868, the population had risen to 22,000. Roads and other infrastructure had been created and there were new towns.

In Hay Street the new Perth Town Hall gave a touch of metropolitan dignity and a promise of more to come.

New areas and industries such as pearling were opening up, as was the south west. Albany, which had been trembling on the edge of extinction, looked like surviving.

The Catholic population of Western Australia – convicts, guards, ex-convicts and new free settlers, had also increased dramatically and the whole Church establishment was moving to a more rational and economically viable basis.

Further, the ludicrous and tragic schisms associated with Bishop Brady had fizzled out with his departure.

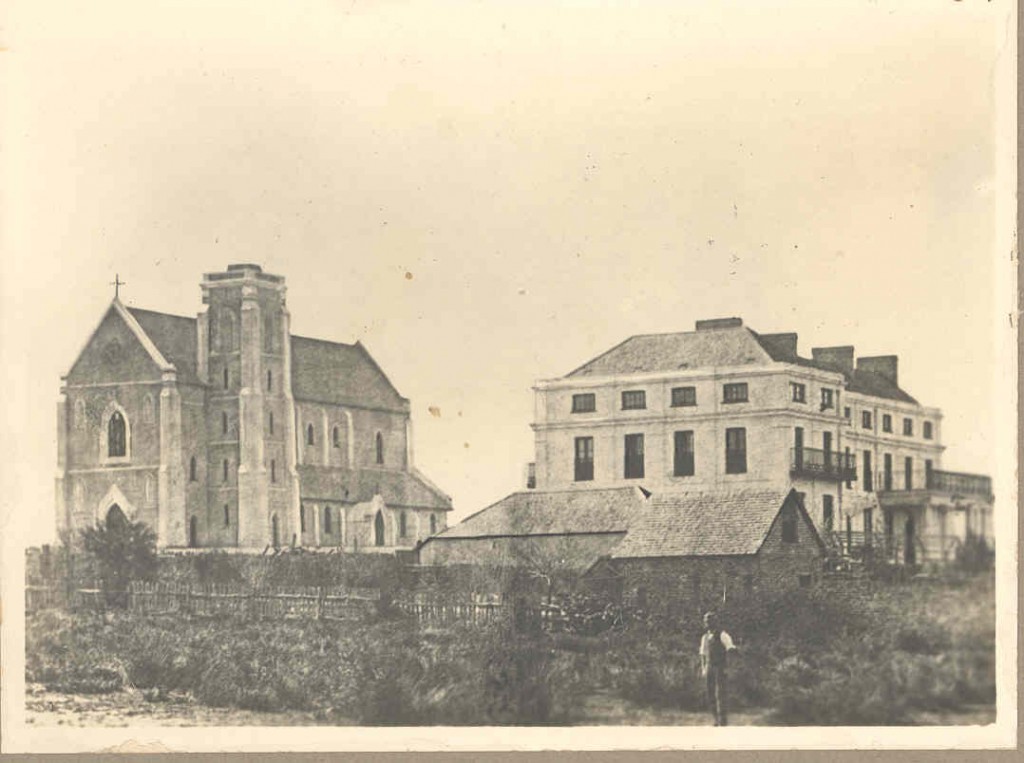

There was a proper cathedral and a number of other substantial church buildings, including the monastery of Subiaco. Development remained relatively slow until the great gold discoveries – by 1889 the European population was still only 43,000 in Western Australia – but the corner had been turned and the settlers no longer had to live in quite such an extremity of isolation.

In 1871, the European population of Western Australia had numbered 23,315, plus 12,470 convicts.

Of these nearly half were Western Australian-born, and 3,569 had been born in Ireland. The Catholic population, again exclusive of convicts, numbered something over a quarter at 6,674, of whom 2,490 lived in Perth and Fremantle, being more than a quarter of the total of 8,220.

This was a very different situation to that when Bishop Brady brought out the first group of missionaries.

Albany’s Catholic population numbered 414 out of 1,585 and there was also a surprisingly large Catholic population of 908 out of a total of 2,472 at Toodyay. York also had a substantial Catholic population of 627 out of 2,493.

In the Greenough and Irwin region, Catholics numbered 528 out of 1,557.

These were congregations big enough to maintain small churches and schools.

Written at a slightly later date, the poem Said Hanrahan, and other writings by ‘John O’Brien’ (Monsignor PJ Hartigan), give a wryly humorous picture of Catholic farmers.

An Anglican clergyman, CHS Matthews, writing of his experiences in Australian country towns in the book A Parson in the Australian Bush, remarked that “to our shame” the Catholic churches were generally the most impressive and best-maintained church buildings.

Then, in 1898, the vast new diocese of Geraldton, probably the largest in the world, was created. It contained about 7,000 Catholics.