By Mark Pattison

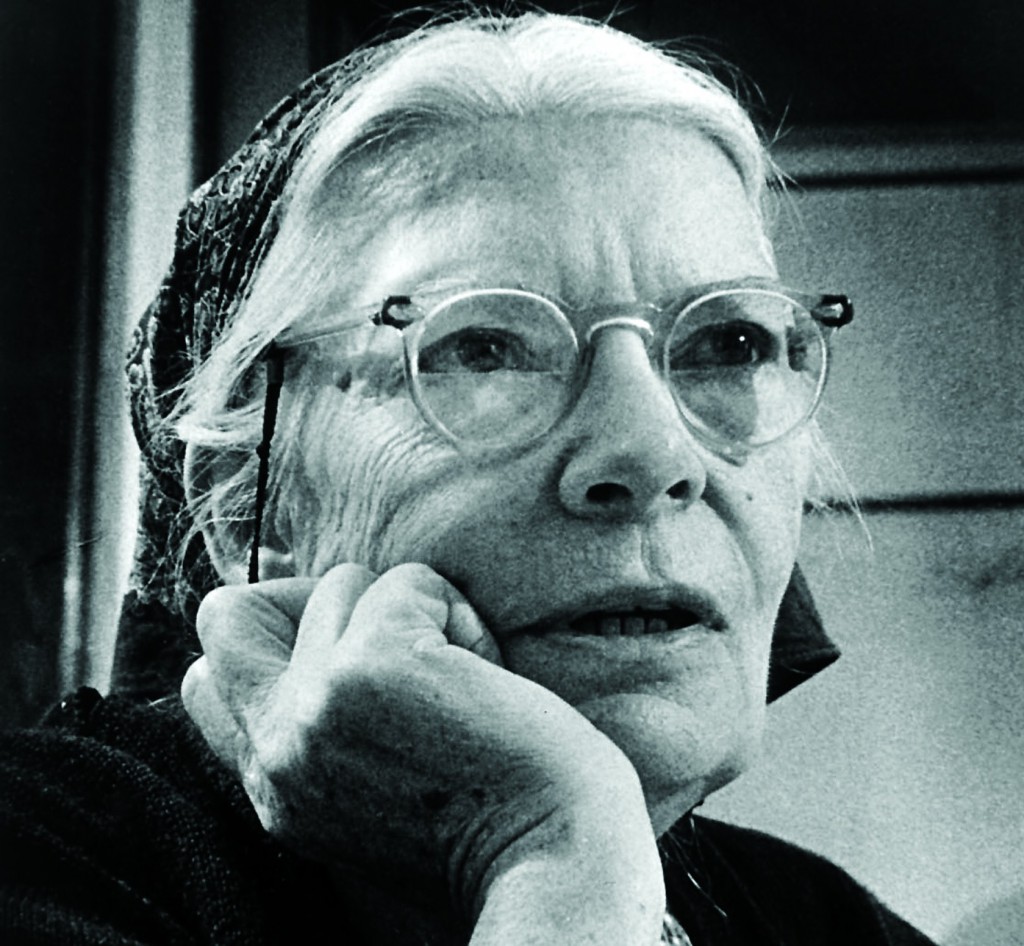

The US bishops, on a voice vote, endorsed the sainthood cause of Dorothy Day, the co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, who was famously quoted as saying, “Don’t call me a saint. I don’t want to be dismissed so easily.”

The endorsement came at the end of a canonically required consultation that took place on November 13, the second day of the bishops’ annual fall general assembly in Baltimore.

Under the terms of the 2007 Vatican document Sanctorum Mater, the diocesan bishop promoting a sainthood cause must consult at least with the regional bishops’ conference on the advisability of pursuing the cause.

In the case of Day, whose Catholic Worker ministry was based in New York City, the bishop promoting her cause is Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York, president of the US bishops’ conference.

The cause was first undertaken by one of Cardinal Dolan’s predecessors in New York, Cardinal John O’Connor.

Cardinal Dolan had earlier conducted a consultation with bishops in his region, and subsequently chose to seek a consultation with the full body of US bishops.

He and the other bishops who spoke during the consultation, some of whom had met Day, called her sainthood cause an opportune moment in the life of the US Church.

Cardinal Dolan called Day’s journey “Augustinian,” saying that “she was the first to admit it: sexual immorality, there was a religious search, there was a pregnancy out of wedlock, and an abortion. Like Saul on the way to Damascus, she was radically changed” and has become “a saint for our time.”

“Of all the people we need to reach out to, all the people that are hard to get at, the street people, the ones who are on drugs, the ones who have had abortions, she was one of them,” Cardinal Theodore McCarrick said of Day.

The retired archbishop of Washington is a native New Yorker.

“What a tremendous opportunity to say to them you can not only be brought back into society, you can not only be brought back into the Church, you can be a saint!” He added.

“She was a very great personal friend to me when I was a young priest,” said Bishop William Murphy of New York. “To be able to stand here and say yes to this means a great deal to me.”

Bishop Alvaro Corrada del Rio of Mayaguez, Puerto Rico, recalled being assigned to Nativity Parish in New York City in the 1970s.

“I had the privilege of being in that parish for the last years of her life … Her final days and suffering” and her 1980 funeral.

The work of the Catholic Worker movement is still active 80 years after Day co-founded the movement with Peter Maurin.

There are many Catholic Worker houses in the United States, some in rural areas but more in some of the most desperately poor areas of the nation’s biggest cities.

They follow the Catholic Worker movement’s charism of voluntary poverty, the works of mercy, and working for peace and justice.

The Catholic Worker, the newspaper established by Day, is still published regularly, and still charges what it did at its founding: one penny.

“I read the Catholic Worker when I was in high school and I’ve read it ever since,” said Cardinal Francis George of Chicago. He recalled meeting Day soon after the 1960 presidential election.

“I had just voted for the first time, for John F. Kennedy. I listened to her critique of our economic and political structures. I asked her, ‘Do you think it will help having a Catholic in the White House who can fight for social justice?’

“She was very acerbic. She said, ‘Young man’ – I was young at that time – ‘young man, I believe Mr Kennedy has chosen very badly. No serious Catholic would want to be president of the United States.’ I didn’t agree with her at that time. And I’m not sure I agree with her now.”

Day’s early life was turbulent and unsettled. She was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1897, but her family soon moved to San Francisco, where she was baptised an Episcopalian.

Her family later moved to Chicago, and Day attended the University of Illinois in Urbana.

However, she left college to go to New York City to work as a journalist.

While in New York, she got involved in the causes of her day, such as women’s suffrage and peace, and was part of a circle of top literary and artistic figures of the era.

In Day’s personal life, though, she went through a string of love affairs, a failed marriage, a suicide attempt and an abortion.

But with the birth of her daughter, Tamar, in 1926, Day embraced Catholicism.

She had Tamar baptised Catholic, which ended her common-law marriage and brought dismay to her friends.

As she sought to fuse her life and her faith, she wrote for such Catholic publications as America and Commonweal.

In 1932, she met Maurin, a French immigrant and former Christian Brother.

Together they started the Catholic Worker newspaper – and later, several houses of hospitality and farm communities in the United States and elsewhere.

While working for integration, Day was shot at. She prayed and fasted for peace at the Second Vatican Council. She died in 1980 in Maryhouse, one of the Catholic Worker houses she established in New York City.

She has been the focus of a number of biographies. Other books featuring her prayers and writings have been published.

In the 1990s, a film biography Entertaining Angels: The Dorothy Day Story starring Moira Kelly and Martin Sheen, made its way into US theatres.- CNS