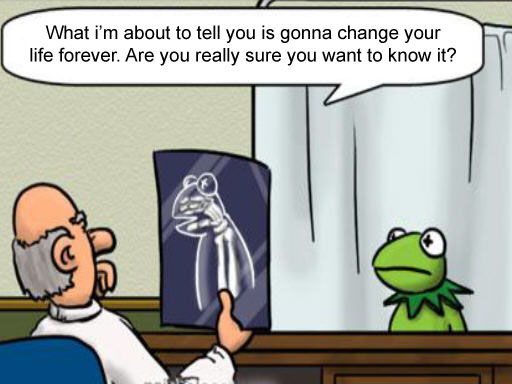

There is a cartoon image which shows Kermit the frog visiting the doctor.

The doctor is examining an x-ray of Kermit which shows that it is actually a human hand animating the frog’s body.

In the speech bubble, the doctor is seen to say, “Have a seat Kermit. What I’m about to tell you may come as a big shock”.

All these years Kermit has been busy hosting the Muppet Show, meeting celebrities and avoiding the romantic advances of Miss Piggy, but his understanding of himself was completely wrong.

To some extent, we are no different to Kermit: we go about life, interacting with the world around us, making our decisions based on certain assumptions that we often don’t even realise we have. Everyone views the world through some sort of lens, we are all a canvas that started being painted upon before we were born.

This canvas is influenced by factors which include our family, our friendships and our faith.

With the increasing secularisation of society, though, you may have sensed the push for an a-religious attitude to matters of politics, education and public life in general.

The problem with this, though, is that a non-religious ethic is no more neutral than a religious one.

Every view of life is underpinned by a certain philosophy which steers an idea like a captain steers a ship.

In our pluralist society, there are almost as many ‘isms’ as there are people, philosophies such as relativism, communism, rationalism or feminism.

These are all different ideas about life, thought and action.

Not all the ideas in the marketplace of thought are completely wrong or completely right: most errors stem from a truth that has been pushed too far one way or the other.

It would be worthwhile looking briefly at four of the major schools of thought that underpin many current ideas held about the human person – Dualism, Manichaeism, Utilitarianism and Personalism.

In the late Middle Ages, a chap named Rene Descartes embarked upon a quest to discover those things that he could be absolutely certain about.

In doing so, he became convinced that the mind was all he could be sure of, and from him came the famed phrase, ‘I think, therefore I am’.

This dualist split between the mind and the body has become one of the most prominent signs of thought in our postmodern world.

Consider the results if we are only our minds and our bodies are little more than machines.

Manichaeism stems from an ancient religion in which two equal powers of good and evil fought out in each person for control.

The good power was considered the soul composed of light, and the evil power was considered the body composed of darkness.

A person would be able to save themselves in so far as they transcended the body.

While the Manichaean religion no longer exists, the transcending of the body concept exists on in Hinduism and Buddhism and a host of New Age spiritualties.

Another popular idea is Utilitarianism which says that the worth of an action revolves around its usefulness.

An action can switch from being wrong, right or morally neutral depending on the resulting value of the idea.

This philosophy is often seen when science is crossing a new frontier that may have corresponding ethical concerns.

Some years ago, when embryonic stem cell research was being discussed, the acceptance of the science was hinged completely on the stories of the many illnesses it was purported to cure.

Personalism goes back to the ancient Greeks and seeks to describe the human person as having a unique value and free will, asserting that only persons exist as true subjects and not as objects.

While this philosophy is not Christian in its origins, it is what Christianity has built its concept of the human person upon.

In Personalism, all persons are real with a body and a spirit and have an innate dignity.

These philosophies are only four but they form the framework of so many ethical and moral positions, including the most controversial.

It is certainly worth taking the time to consider not just these philosophies but the fruits which come from them.

Each of us is guided by one or more philosophical ideas so best we know what they are.

We may live in a pluralistic age but unless we have made clear decisions about what we wish to stand for, we may be shocked to one day discover that we were no wiser that Kermit the frog.