I remember as a young boy watching the black-and-white Alfred Hitchcock Presents on TV and being enthralled from the start by the simple nine-stroke line-drawing caricature of the famed movie director’s rotund profile.

The mischievous theme music set the mood as Hitchcock appeared in silhouette from the right edge of the screen, and then walked into the centre, replacing the caricature.

“Good evening.” There followed his droll introductions, so unlike anything else on television.

Such childhood emotions came over me again when, in early 1980, I entered his home in Bel Air to see him dozing in a chair in a corner of his living room, dressed in jet-black pyjamas.

At the time, I was a graduate student in philosophy at UCLA and I was (and remain) a Jesuit priest.

A fellow priest, Tom Sullivan, who knew Hitchcock, said one Thursday that the next day he was going over to hear Hitchcock’s confession.

Tom asked whether on Saturday afternoon I would accompany him to celebrate Mass in Hitchcock’s house.

I was dumbfounded but, of course, said yes. On that Saturday, when we found Hitchcock asleep in the living room, Tom gently shook him.

Hitchcock awoke, looked up and kissed Tom’s hand, thanking him. Tom said, “Hitch, this is Mark Henninger, a young priest from Cleveland.”

“Cleveland?” Hitchcock said. “Disgraceful!” After we chatted for a while, we all crossed from the living room through a breezeway to his study and there, with his wife, Alma, we celebrated a quiet Mass.

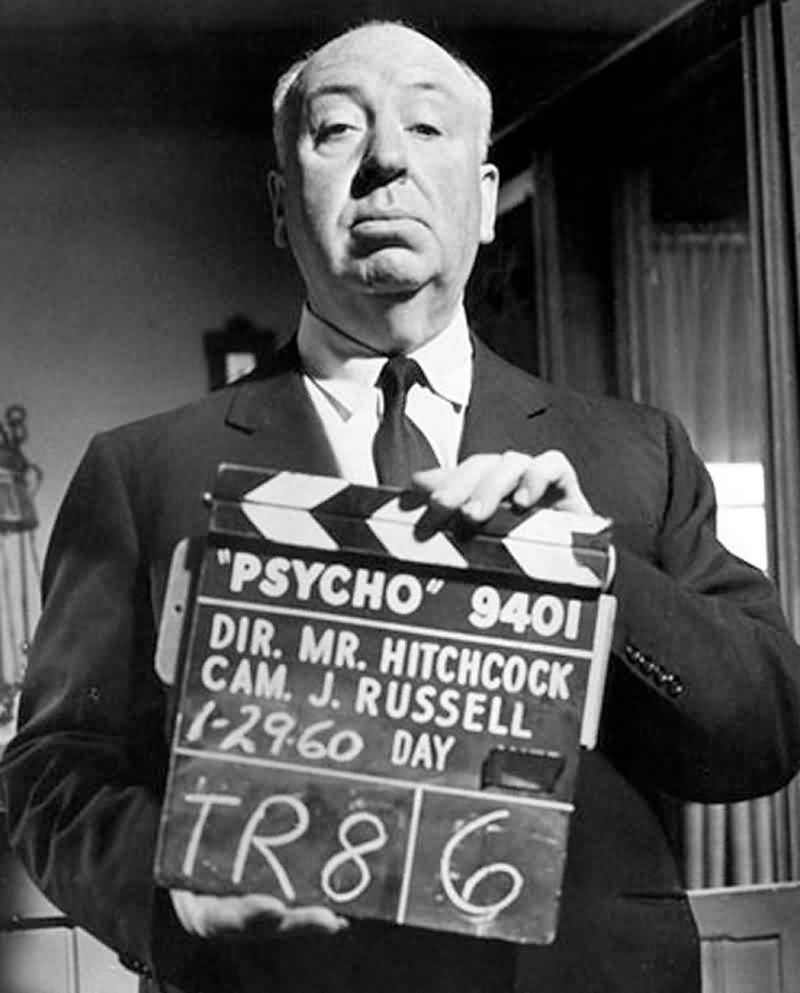

Across from me were the bound volumes of his movie scripts, The Birds, Psycho, North by Northwest and others – a great distraction. Hitchcock had been away from the Church for some time, and he answered the responses in Latin the old way.

But the most remarkable sight was that, after receiving Communion, he silently cried, tears rolling down his huge cheeks.

Tom and I returned a number of times, always on Saturday afternoons, sometimes together, but I remember once going by myself.

I’m somewhat tongue-tied around famous people and found it a bit awkward to chitchat with Alfred Hitchcock, but we did, enjoyably, in his living room. At one point he said, “Let’s have Mass”.

He was 81 years old and had difficulty moving, so I helped him get up and assisted him across the breezeway.

As we slowly walked, I felt I had to say something to break the silence, and the best I could come up with was, “Well, Mr Hitchcock, have you seen any good movies lately?”

He paused and said emphatically, “No, I haven’t. When I made movies they were about people, not robots. Robots are boring. Come on, let’s have Mass.”

He died soon after these visits, and his funeral Mass was at Good Shepherd Catholic Church in Beverly Hills.

Alfred Hitchcock has returned to the news lately, thanks to an apparently unflattering portrait of him in a new Hollywood production.

Some of his biographers have not been kind, either.

Religion, too, is much in the news, also often presented in an unflattering light, because clashing beliefs are at issue in wars and terrorism.

The violence provokes some people to reject religion altogether.

For many who experience religion only in this way – at second hand, in the media, from afar – such a reaction is to a degree understandable.

What they miss is that religion is an intensely personal affair.

St Augustine wrote: “Magnum mysterium mihi” – I am a great mystery to myself.

Why exactly Hitchcock asked Tom Sullivan to visit him is not clear to us and perhaps was not completely clear to him.

But something whispered in his heart, and the visits answered a profound human desire, a real human need. Who of us is without such needs and desires?

Some people find these late-in-life turns to religion suspect, a sign of weakness or of one’s “losing it.”

But nothing focuses the mind as much as death.

There is a long tradition going back to ancient times of memento mori, remember death.

Why? I suspect that, in facing death, one may at last see soberly, whether clearly or not, truths missed for years, what is finally worth one’s attention.

Weighing one’s life with its share of wounds suffered and inflicted in such a perspective, and seeking reconciliation with an experienced and forgiving God, strikes me as profoundly human.

Hitchcock’s extraordinary reaction to receiving Communion was the face of real humanity and religion, far away from headlines … or today’s filmmakers and biographers.

One of Hitchcock’s biographers, Donald Spoto, has written that Hitchcock let it be known that he “rejected suggestions that he allow a priest … to come for a visit, or celebrate a quiet, informal ritual at the house for his comfort.”

That, in the movie director’s final days, he deliberately and successfully led outsiders to believe precisely the opposite of what happened is pure Hitchcock.

Reprinted with permission of The Wall Street Journal © 2012 Dow Jones & Company. All rights reserved.